Abby Leigh’s visible work seduces with subtle, unassuming color and flashes of silvery metal. We look at these paintings, and it is as if we were peering into a microscope at a specimen displayed on a slide. When our eye gazes through the lens, the specimen becomes the world. Leigh makes the microcosm of the slide metamorphose into the macrocosm. Which is to say, with her work we can—as we cannot with the microscope—step back and see them at a distance, effect our own metamorphoses, and make them into landscapes, the night sky, an undersea world.

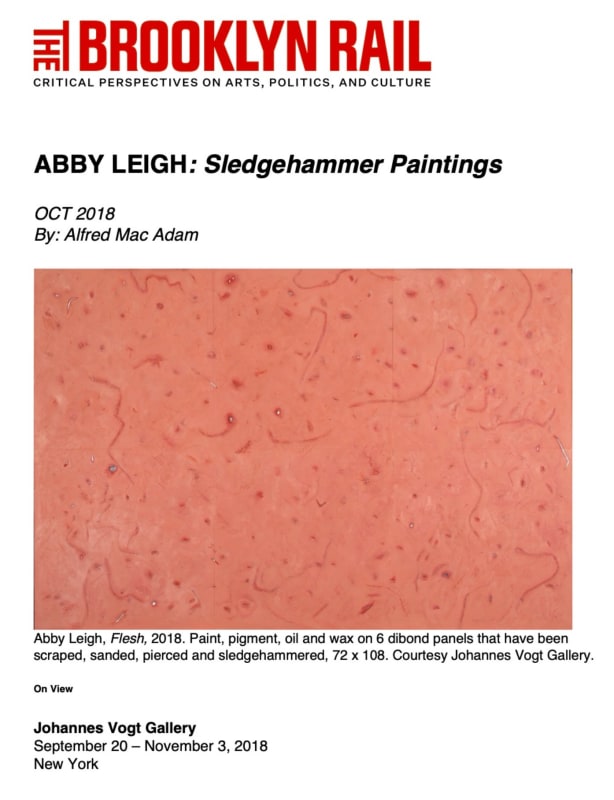

But there is more to these paintings than meets the eye: literally. We cannot see the invisible work, the process that culminates in the painting on the gallery wall, but that should interest us as much as the finished product. Leigh begins with dibond, which consists of two sheets of painted aluminum .012 inches thick, which enclose a polyethylene core. She has the dibond cut to specific sizes so she can deal with each panel individually or, as she does in the splendid Flesh (2018, 72 × 108 inches) join panels. She assaults the dibond surface, which is perfectly flat, by sanding it, effectively creating a new, imperfect surface. She then applies a coat of dark pigment, she allows to dry and cure. Next she attacks the surface—hence the show’s title Sledgehammer Paintings—effectively sculpting it. Then comes oil paint, with the inevitable reworking that includes repainting and exposure of the raw aluminum below.

The result of this labor-intensive, ritualized practice is a surface unlike any other with tremendous variation from piece to piece, most especially between small and large-scale works. Competitive Skies 2 (2018) is 18 × 24 inches, and its pale blue hue might indeed suggest the sky, but this sky has been through a great deal, and it is a highly convoluted surface with dents and ridges. In fact, it seems to invite touching, which would doubtlessly ruin the patina of the slow-drying paint. To appreciate the differences among these works, we should compare the visual effect of that smaller piece to a medium sized example like Black Hole (2018, 36 × 36 inches). Here the surface irregularities lose importance, and we are carried away into the void, the cosmos, dotted with the silver stars of exposed aluminum.

Flesh is the show’s tour-de-force. Composed of six dibond panels subjected to Leigh’s esthetic abuse, it is what its title suggests. How Leigh manages to turn distressed dibond and paint into an erotic experience is impossible to fathom, but this huge painting, which the viewer must see from at least three distances, evokes a world of desire. Unlike banal abstraction, this work takes the viewer back to the erotics of landscape, the fetishizing of nature that transforms mountains and trees into voluptuous bodies. Flesh makes us acknowledge the sexual charge latent in traditional landscape painting and in this brilliant reinvention of it. Abby Leigh has created a brave new world for abstract painting.